Polar Bears, Penguins And Bone Marrow Transplants

- Aug 12, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Aug 13, 2025

A Canadian woman who survived an experimental bone marrow transplant, an Austrian researcher who studied polar bears and penguins, a retired British-born librarian who gained his university degree in his 60s and a new first-time mother and English teacher from a small town in Ohio.

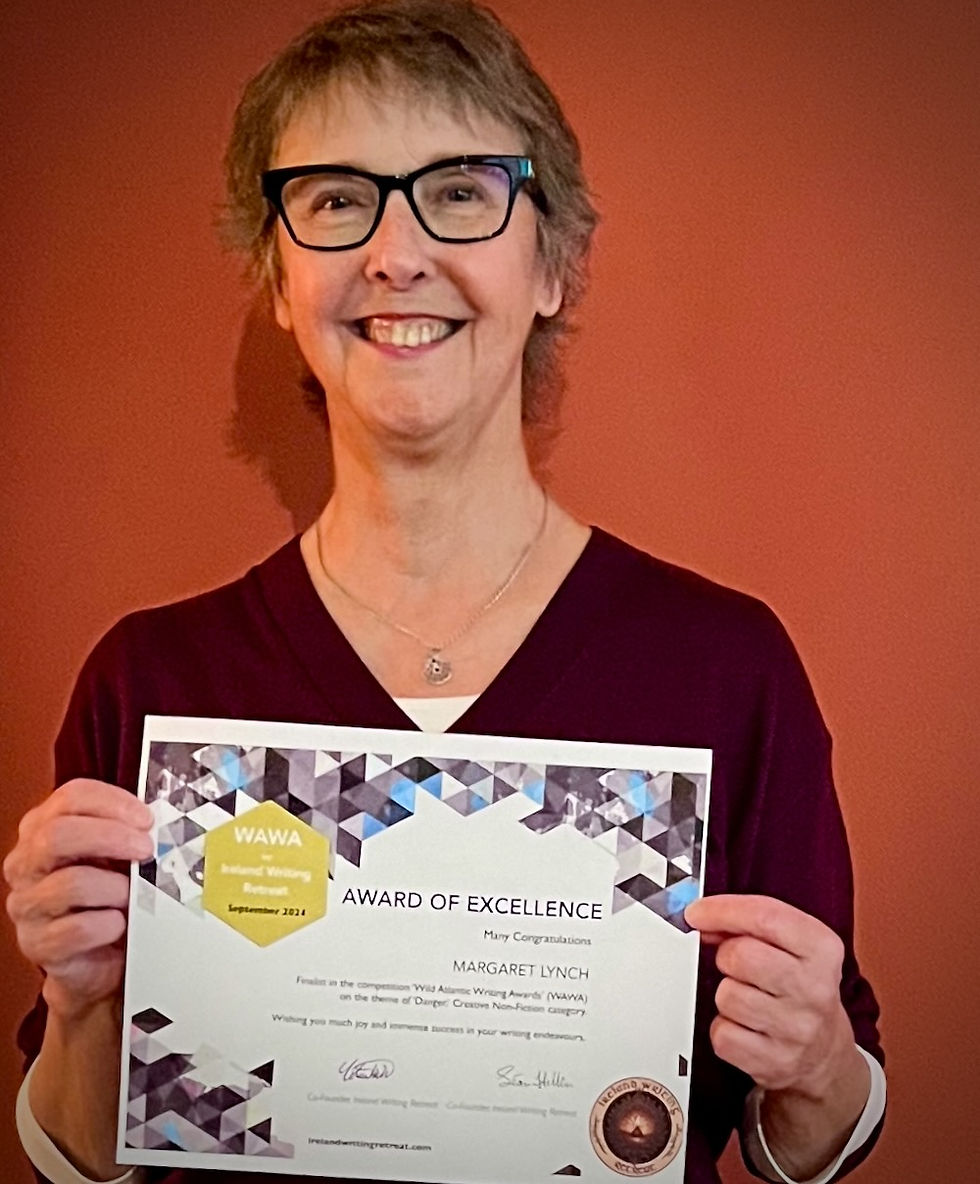

Meet Margaret Lynch, Viktoria Valenta, David Kipling and Maggie Thomas, all finalists in our ‘Wild Atlantic Writing Awards’ competition on the theme of ‘Danger.’

And for those interested in exciting international author-led writing workshops on both flash fiction and creative non-fiction combined with cultural tours, exclusive music performances and food tastings this autumn, remember you can still join us in September in Donegal and in October in Belfast.

Margaret Lynch

Having survived an experimental bone marrow transplant that transformed her life, Margaret Lynch knows how close death can be.

And that has given her the strength and will-power to pursue her love of creative writing, thus being “thrilled and humbled” as a finalist in WAWA’s non-fiction category with her story ‘Sacrifice.’

Born to parents who emigrated to Canada from different parts of Ireland, Margaret, 67, lived in New York during the 1980s and is now based in Toronto.

Following a successful IT/digital marketing career, her creative writing journey began ten years ago and has blossomed ever since.

Her work has appeared in The Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, National Post, CBC Radio, and literary magazines including Untethered, The Examined Life and 805 Lit + Art. She also won the 2020 Penguin Random House Canada Book Proposal Prize for her memoir.

As for her WAWA story.

“The impetus was a writing class prompt to craft a scene evoking a sense of childhood,” she said. “I revised it a few times to balance dialogue and exposition to heighten the sense of tension, including naming characters with labels commonly used in the Catholic Church. I tried to capture the innocence of the children, while showing the danger they lived with.”

She added, “True stories fascinate me which is why I’m drawn to write memoir, the reward for revealing myself being a sense of connection, that we’re all more alike than different. I like stories hidden beneath the surface of everyday life.”

Initially entitled ‘Friday,’ Margaret changed the name to ‘Sacrifice’ after highlighting a crucifix in her story.

Sacrifice

by Margaret Lynch

On a day that could have been any day of my early childhood, I sit beside Brother on the concrete ledge at the rear of our house facing the laneway. His elbow digs into my ribs. Younger Sister walks in circles around the empty parking spot, kicking up dust from small grey stones and scuffing her white Mary Janes.

The back door opens and we turn, startled. Mother leans out. “Is Father home yet? Tell me when he gets here. I want to talk to him first.” She slams the door behind her and goes inside to finish dressing. We’re hungry, but nobody can eat until he gets home.

“I think we were good today,” says Brother.

“Yeah, not like the time I fed you cigarettes.” That was last year when I was five and he was four. I can’t believe he ate them.

“How do Mother and Father eat them all day long? I got sick after eating two.” His face scrunches up at the memory.

“It’s the fire. They use lighters to cook them first. We’ll try that next time.”

“What do you think she’ll tell him?” He scissor-swings his legs, eyes forward.

“Who knows? She didn’t yell at us too much,” I say. “At least you didn’t lie after you pulled Sister’s hair.”

Tires crunch gravel as Father’s taxi appears in the laneway and turns into the parking spot. I’ve memorized the round sign on top of the black and white Biscayne: Metro cab EM.3-5611. If there’s an emergency, I know to phone that number and ask for him.

Mother flies out the door and runs past us to kiss him before we have a chance to say anything. He steps out of the taxi—tall and muscular with slicked-back dark hair—handing over his empty lunch pail and thermos. She wears a cornflower blue dress that matches her eyes, with a flared skirt, short sleeves, and collar. The little white buttons above the waist are all done up except for the top two which show off the crucifix hanging from a chain around her neck. She wears it to honor the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, who died on the cross for our sins.

She complains about how noisy we were and who hit who, and who cried.

Father looks at us for the first time. “Don’t you know children should be seen and not heard?”

“Yes,” we chime in unison. We’ve heard it often enough.

He’ll have dinner first, he says, and think about the right punishment, as if there’s a chart somewhere in his head. We know it will be three or four slaps with his meaty hand. Always on the bum, so no one else can see. In a few years, there will be a belt, a Calgary Stampede souvenir, handmade and tan-colored with a thick oval brass buckle that will leave hidden bruises.

The door opens and he follows Mother into the house. I smell fish. It must be Friday.

Maggie Thomas

A 29-year-old English teacher in Mansfield, Ohio, and first-time mother, Maggie described being a finalist in WAWA’s flash fiction category with her story ‘Periphery’ as “confirmation and inspiration to keep writing and dreaming.”

Her award was even more special as it was her first-ever international writing competition.

After completing a Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing, English, Public Relations and Strategic Communication at Ashland University, she then achieved a Masters degree in Creative Writing there. One of her nonfiction stories was published in A Gathering of Flowers: An Anthology in Essay and she is working on a draft of her first novel.

As for her WAWA story, she said, “The idea was sparked by a college professor pointing out that something more sinister might be going on in the bookstore than what I had originally intended in a scene I was writing,” she said. “I just kept going until I figured out exactly what kind of monster lingered there.”

Initially, Maggie’s story was meant to be a prologue to her novel-in-progress. “After deciding to cut it from the novel project, it took months to make it more of a stand-alone story,” she added. “The most difficult challenge was maintaining the balance between revealing information and keeping some elements unanswered.”

Maggie said she chose her title ‘Periphery’ because “it felt right physically for the scene, as well as in a literary sense. I was searching for a word to capture that feeling of leaving, on the edge of something, the outside of symbolic circles.”

Periphery

by Maggie Thomas

Broken glass, the bones of the bookstore, crunched under Lenna’s feet. Her shocked cry barrelled off the barren shelves and broken plaster, silenced by the whispers of smoke. The skin on her knuckles stretched and turned white from holding herself up on one of the shelves.

He fucking knew.

Only sheets of dust, glass, the register, and the broken coffee machine had survived his rage. He had locked her in the back office, a soundproofed room once designed as her mother’s writing space. She’d been in there for hours before remembering the spare key hidden on the underside of the desk.

Grabbing a large piece of glass from the floor, heat coursed along the sides of Lenna’s neck. She worked her way to the other side of the counter and squatted behind the register with her glass shiv at the ready.

Only from her hunched position did she see the large ring singed onto the wooden floor, black ash in a perfect circle. Looking at it, she could feel his hands around her throat. She could feel his cigarette on the inside of her wrist. She could feel his round knuckles connecting to her cheekbone. All of it, the ring – a symbol, his symbol for her. Where anger had once flowed hot beneath her skin, she now felt the icy chill of fear.

Shaking, she tore her gaze from the ring on the floor to finally acknowledge the plume of smoke outside of the back shattered window. She could smell it, heavy and stale. Low visibility kept the back lot hidden, but if she could get to her car in the front, she could still make it.

Stepping outside, fear manifested as a pair of hands around her lungs. Earlier that morning, Lenna left the keys under the driver’s side tire, the jingling now like a warning bell as she rammed them into the side of her car. The car roared to life, but before pulling away, Lenna took another look at her mother’s bookstore – a place that held her grief, but also held her bruised body on the floor. The bookstore now looked like a skeleton of what it once was; she supposed she did too. The sign, broken in two, swayed in the breeze and banged ever so slightly against the storefront as if pleading with her for help.

Lenna pulled the car forward, daring a glance behind the bookstore before hitting the gas. Twenty feet away, by a sea of tall grass waving back and forth at her, the monster stood before a giant pile of burning debris. He saw her, but didn’t move. In books, monsters have fangs, claws, fur, spikes, or scales. The monster before her looked nothing like them. He had skin. She peeled the car away, half-expecting him to start running down the road after her. In the rearview mirror, she could see the outline of him watching her, waiting, fading into the night.

David Kipling

Born on a farm in the British Midlands, David, whose story ‘Quarry’ earned him a finalist place in the flash fiction category, has worked many jobs in his 78-year life including railway telecomms installer, office clerk, warehouse labourer, librarian and college instructor at the British Columbia Institute of Technology.

And in places as varied as Northampton, London, Bristol, Montpellier and Vancouver.

Proud to have gained his Bachelor’s degree in his 60s from the University of Alberta, David is a lifelong motor sport fan, having been a drag racing announcer for many years. He runs an archival website on British stock-car racing history, and has written many articles on motor sport.

As for his WAWA story, “It was written probably ten years ago and triple the length so this proved to be mainly an editing exercise,” he said. “But reducing it to flash fiction took me only a day. I threw out everything but the girl Rachel from my original and in doing so uncovered my real story. I often write about women with bold exploring minds and as I grew up with shotguns and rifles, they intrinsically interest both myself and my women characters.”

His title is ambiguous. “The noun ‘quarry’ has two very distinct meanings, and I mean them both,” he said.

As for writing challenges, “Finding that fine line between saying too much and patronising the reader and holding back so much that the readers is puzzled,” he said. “My nature is to fear readers need more, while my betters assure me they are much smarter than me. I’m also addicted to tinkering and editing.”

Though flattered, reassured and encouraged were the words David used to describe hearing the good news he was a finalist, he also said he was horrified. “Horrified to learn my writing is to be published because I’m bound to find better words and sentences that I could have used and wish I had: the writer’s dilemma.”

A lover of modern jazz and classical music, David is also involved in community reading and writing groups at The Electric Mermaid in Port Alberni and the Open Mic sessions at Gibsons Public Library.

Quarry

by David Kipling

Out of the blue, Rachel remembered the kick of the shotgun. She fitted the lens cap on her theodolite and pencilled the angle into her logbook, when a bang racketed across the marshland.

The road ran straight as a die, and flat, as it should on these wetlands. Waterfowl country. Nothing between here and Holland, but wind, and birds.

Bang. Again. A hunter somewhere out on the flats. Her survey crew’s yellow vests, and orange cones on the narrow road announced their presence. Should be little risk to them, from guns, today, just as to her father then.

Rachel remembered the kick of the shotgun.

When Rachel had turned fourteen, something insisted there was another stage, beyond the BB gun that had awakened her early fascination with geometry and physics, when she had punctured paper targets on farm gateposts.

Tom Blake’s shotgun slept in a wood and canvas case in the boot room. Rachel drew it out and sniffed at the film of oil around the breech. She weighed a cartridge in one hand, fingering its waxy red casing, trying to sense the death she knew was in it.

She took a breath and called out to her father in the garage, “Can I fire the shotgun, Dad?” Tom Blake stepped into the house and looked down at her. She stood her ground and looked back at him. It felt scary. “Okay, come over to the quarry. I’ll show you how.” Rachel felt a cold breath move inside her, like her first time on the top diving board.

At the quarry, Tom made her watch while he opened the gun.“Look close. Empty: safe.” Then he loaded the gun, snapped it shut, and looked at her, hard. “Loaded: kills.” Rachel had never forgotten the urgency in his voice.

He swung the barrel straight at the limestone cliff, and fired. Her stomach and legs flinched under her summer frock. It was like being smacked. Her father made her watch as he extracted the smoking spent cartridge and loaded the next. “There now, your turn.”

She tested the moment and asked, “Dad, could I shoot a bird?” Tom looked steadily at her. “Do you want to?”

“You’ve shot crows. What was it like?” Tom shook his head, “I can’t say; I’m not you.”

Rachel selected a crow pecking among the rocks. She hefted the gun to her skinny shoulder. Her father loomed beside her.

“Hug the gun. The harder you hug it, the less it bruises,” her father cautioned. “Same as your air gun, remember? Breathe in--little pressure on the trigger--breathe out and pull.”

The bird had eyes just like her father’s, that had peeked coldly at her through her window when she was dressing. She squinted, breathed in, little pressure, and breathed out. Her plastic sandal slipped on a loose rock, and, falling carefully backwards, as though by accident, she pulled, hitting her target between the eyes, just as this hunter did today.

Viktoria Valenta

A globe-trotting researcher whose travels took her from Canada to Chile and beyond, Viktoria earned a finalist’s place in the creative non-fiction category of WAWA with her ‘storming’ adventure story entitled ‘Bear Island.’

Born and raised in Austria, as a biologist Viktoria, 34, has experienced a wide variety of flora and fauna from rainforests to deserts, polar bears to penguins. But she is always drawn back to Vienna to the city where she grew up and where she feels there is a lot to discover. Now she is a researcher and project leader in forest science.

As for her WAWA story, she said, “It is based on a pretty intense memory that I never before tried to put into words. It was challenging not to go into all the details but still convey what it was like out there on an unforgiving ocean.”

She added, “The story took a surprisingly short time to write and redraft. As I only found out about the competition a day before the deadline, the pressure was on, and I redrafted three times until I had the feeling and word count right.”

Her title proved easy to choose. “For me, there are so many memories associated with the title that I did not want to take away from it.”

Her first time submitting a non-fiction story to a competition, Viktoria was surprised seeing her name on the finalists’ list. “It was such a joy reading the email,” she said. “I had goosebumps.”

Bear Island

by Viktoria Valenta

My heart was beating fast, shaking my whole body. I had nine or maybe ten people on my zodiac. Actually, ten - there was no "maybe" when you were north of the Arctic Circle. You counted your guests, at least twice - in case the boat tipped over. And I had never come so close as on that deceptively sunny day at Bear Island.

Driving a zodiac around cliffs and caves, searching for whales and puffins was all very picturesque, very adventurous. But the radio at my ear told me it was time to head back. There was a storm on the horizon and out here in the middle of the Norwegian Sea it was getting choppy.

“Ewey, where are you?” I called my zodiac buddy.

“Coming up on your right. We need a plan.” I could see the frown behind his goggles.

“Into the storm?” I asked hesitantly.

He nodded. “It’s a bit of a detour, but the waves will be smaller –”

“– and the chances of being smashed onto a boulder,” I added in my mind.

“Hold onto the ropes and lean towards the middle of the boat as much as you can,” I urged my passengers. “This is going to be rough!”

The next thing I remember was staring at a monster. Well, a standing wave, a surfer's paradise – several metres high and seemingly frozen in place. My heart was racing. We had to find a way up and – crucially – safely down from that thing.

Ewey took his time analysing the wave. And I used that moment to panic. I had never seen anything like this, had only recently started driving boats, and now I was responsible for the lives of “seven, eight, nine, ten” people in my boat. I counted again.

“Ok, I’ll show you where,” Ewey was hovering beside me again. “Follow where I go – but wait with the drop until I’m on the other side.”

He looked at me intently. This was important. We couldn’t have two overturned boats at the same time.

I wiped the rain off my goggles and watched Ewey disappear. I felt this emptiness in my stomach that always appeared when my world was about to end. I swallowed, then followed the invisible path Ewey had ploughed into the water.

My body rocked with the mood of the ocean. My knees shook. But I had to focus on the precise spot from where to drop. Smoothly, but with momentum, we reached the top of this watery barricade, and with another burst of speed we breached.

It took me a couple of seconds and about fifty meters to realise we had done it. With a weight falling from my chest, I sidled up to Ewey’s boat and turned around to look at the monster.

“It doesn’t look that bad from the other side, right?” Ewey grinned.

“Right,” I sighed. “Nothing to it.” And from here it really did look like any other rocky wave travelling across the ocean.

Comments